IACMI supports UT-designed face shield production

The UT Shield features lightweight frame and clear plastic that is reusable and easily cleaned for incoming students, faculty and staff.

Photo Credit: IACMI

The Institute for Advanced Composites Manufacturing Innovation (IACMI; Knoxville, Tenn., U.S.) recently reported that it supported the University of Tennessee’s (UT) production of more than 50,000 protective face shields for students, faculty and staff who returned in August as additional protection against the COVID-19 virus.

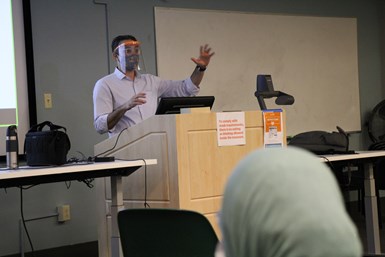

The face shield, called UT Shield, was designed by Maged Guerguis, assistant professor of Architecture and McCarty Holsaple McCarty Endowed Professor at UT’s College of Architecture and Design. Guerguis is also the director of Soft Boundaries a multidisciplinary research laboratory investigating the intersections of architecture, engineering and science.

“I designed the face shield to improve safety and provide comfort for the health care professionals working long hours fighting at the front lines of the pandemic, and I’m honored that it also is being used across campus to help our volunteer community stay healthy,” Guerguis says. Weighing in at only two ounces, Guerguis notes that the clear visor is spaced with maximum clearance from the face to allow for glasses or medical equipment to be worn comfortably. Moreover, the shield assembles in five seconds, doesn’t require an elastic band and includes ergonomic end tips. Hundreds of UT Shields were donated to area medical professionals over the summer.

Switching to injection molding and having a new custom-made tool enabled the team to produce two headbands in less than five seconds.

Accordingly, the 50,000 shields for the UT campus have been produced under the guidance of UT professor Uday Vaidya of the Department of Mechanical, Aerospace and Biomedical Engineering. Vaidya is the UT-Oak Ridge National Laboratory Governor’s chair for Advanced Composite Manufacturing and also serves as the chief technology officer for IACMI.

Vaidya says discussions began in the summer with the UT administration to produce the face shields for the university. He noted that delivering such a large quantity prior to the start of the fall semester was no small task and praised the teamwork from the chancellor’s office, UT Research Foundation, Tickle College of Engineering and College of Architecture and Design as well as IACMI partners to bring the face shields from conception to distribution in such short order.

“It all happened so suddenly and everyone came together quickly,” he says. “Our extended network — people we work with that do everything from fabric work, injection tooling, injection molding, thermo forming — were energized and eager to help. We are fortunate that we have the teamwork and the IACMI network in place to respond so quickly.”

Vaidya also points out to IACMI’s utilization of the organization’s advanced materials, manufacturing experience and network for other projects during the pandemic, including the incorporation of 3D printers.

“Obviously, we could not support making 50,000 face shields before the start of the semester with 3D printing alone,” Vaidya says, noting that even the fastest 3D printer would take up to 30 minutes to produce a single shield headband. “Our team focused on materials and processing and used our know-how for injection molding to design tooling. IACMI’s investments and assets came into play in a major way in production of the shields.”

Guerguis agrees, adding that switching to injection molding and having a new custom-made tool enabled the team to produce two headbands in less than five seconds. “It’s not only faster, but it also produces a superior quality finished product,” he said.

For this project, a two-cavity tool – capable of producing two parts per mold shot – was designed and test frames were produced in black color, although, Vaidya points out, the frames were quickly switched to UT orange, which was the logical choice for the final design. Moldesign Mold Making (Knoxville, Tenn., U.S.) is reported to have produced the tool, which “worked great, allowing us to knock out about 50,000 units in about two weeks.” NewCo3, Inc. (Batesville, Miss., U.S.) the injection molding of the frames.

The shields are packaged flat and distributed in two parts for assembly by the wearer. The clear, plastic shield portion is made from a material called polyethylene terephthalate glycol (PET-G), similar to the material used to make water bottles. Thickness of the shield is about 20 millimeters, or about two-thirds the thickness of a debit card. A portion of the film used in the production of the shield was donated by Eastman Chemicals (Kingsport, Tenn., U.S.), an IACMI partner, while some material was been purchased from other suppliers. Jamison Steel Rule Die Inc. (Murfreesboro, Tenn., U.S.) made the steel rule die for cutting the shield material.

“It’s a clear, crystalline material—in fact, it’s so very clear you can hardly see it’s there,” Vaidya contends. “It is also easily cleaned with soap, water or alcohol wipes.”

Finally, the clear shields were cut to print by engineering students at the IACMI-supported Fibers and Composites Manufacturing Facility and Engineering Annex (FCMF) on the UT campus. The students, led by Vaidya and FCMF engineers Stephen Sheriff and Joe Gausphol, used steel dies equipped with sharp edges in the shape of the visor. The students place the film on the die and when the press is brought down, the material is sheared into the desired shape. There are three location for holes, so the end user simply matches the three holes to the visor frame and makes the attachment.

Related Content

IACMI’s Chad Duty presents SPE ACCE 2025 third keynote

Duty will share the ways in which IACMI, over its 10-year history, has led to successful and commercialized composites technologies in the automotive industry.

Read MoreWinona State, IACMI invest in composites workforce development

First composites hub in the IACMI-managed ACE national training program funds free bootcamps to equip students and community with hands-on composites skills, knowledge.

Read MorePeople in composites: May 2025

IACMI, Ilium Composites, Wrexham University, 47G, Gurit and Thermwood Corp. have shared new hires and promotions in the composites industry.

Read MoreIACMI celebrates 10th anniversary at Members Meeting

Event in Dayton recapped the Institute’s successes, set future goals, celebrated the retirement of COO Dale Brosius and more.

Read MoreRead Next

Ceramic matrix composites: Faster, cheaper, higher temperature

New players proliferate, increasing CMC materials and manufacturing capacity, novel processes and automation to meet demand for higher part volumes and performance.

Read MoreCutting 100 pounds, certification time for the X-59 nose cone

Swift Engineering used HyperX software to remove 100 pounds from 38-foot graphite/epoxy cored nose cone for X-59 supersonic aircraft.

Read MoreScaling up, optimizing the flax fiber composite camper

Greenlander’s Sherpa RV cab, which is largely constructed from flax fiber/bio-epoxy sandwich panels, nears commercial production readiness and next-generation scale-up.

Read More