Composites in the SuperTruck I Initiative

Some of the newest developments in aerodynamic composite components, as well as other composites applications, are an outcome of the US Department of Energy (DOE) SuperTruck I program.

Some of the newest developments in aerodynamic composite components, as well as other composites applications, are an outcome of the US Department of Energy (DOE) SuperTruck I program. The DOE’s interest in long-haul, heavy-duty trucks stems from the opportunity this sector presents to improve freight-hauling efficiency and reduce greenhouse gases. Comprising only 4% of on-road vehicles, heavy-duty trucks consume 18% of the fuel.

A $284 million joint DOE/industry program run between 2009 and 2015, SuperTruck I set out to develop and demonstrate a 50% improvement in overall freight efficiency in Class 8 tractor-trailers. Four industry teams took part: Cummins Inc. (Columbus, IN, US) with Peterbilt (Denton, TX, US), Daimler Trucks North America (Portland, OR, US), Volvo Trucks North America (Greensboro, NC, US) and Navistar Inc. (Lisle, IL, US). The initiative called for 40% of total improvement to come from engine technologies, but structural lightweighting and aerodynamics also played a large role.

The Volvo SuperTruck’s roof, hood and side fairings are made from carbon fiber materials. According to Volvo Trucks USA’s webpage on the SuperTruck, aerodynamic trailer add-on fairings were developed and built by partner Ridge Corp. (Columbus, OH, US), maker of DymondPly and DymondGuard glass fiber-reinforced thermoplastic wall liners and Green Wing Aerodynamic Side Skirts. Navistar (Lisle, IL, US) used CFRP in the cab’s upper body panels, roof, back panel and dash panel. Its partner Wabash National Corp. (Lafayette, IN, US) developed a lightweight trailer that cut 1,525 lb. It also used an aluminum frame but added composite leaf springs to its design, as well as composite sidewalls, closures and support structure for the aerodynamic skirt. Daimler Trucks North America and subsidiary Freightliner (Portland, OR, US) did not detail use of composites in their SuperTruck, except for carbon fiber cabinets in the cab. However, the team did specify a list of lightweighting partners including MSI-ACPT, Maxion Inmagusa (Castaños Municipality, Coahuila, Mexico), Oregon State University (Corvallis, OR, US), Strick Trailers (Monroe, IN, US) and carbon fiber supplier Toray (Tokyo, Japan). The Peterbilt (Denton, TX, US) and Cummins (Columbus, IN, US) supertruck reportedly featured CFRP in the front of the trailer skirts and the trailer front’s “horse collar.”

Though some of the aerodynamic improvements from SuperTruck I have found their way into production vehicles, none of the four SuperTruck I OEMs has announced production applications specifically of composite components developed in the program. For example, asked what composite components Daimler has adopted in past few years, only 3D printing and composite layup for prototypes were mentioned by Justin Yee, the company’s manager of vehicle concepts in advanced engineering, as well as principal investigator for its SuperTruck II work.

Navistar chief engineer of advanced technologies Dean Oppermann notes that the value of the company’s SuperTruck I work is not in a direct path to specific production components. “We now know how much weight reduction we can get out of a piece,” he explains, “and that information feeds into the business case for production applications.” RobertLane, VP of product engineering for Wabash, agrees, saying the SuperTruck I developments “let us look at the technologies that are out there and how they can be brought into the trailer market, but they are not yet cost-effective.”

Though programs like SuperTruck I serve as technology demonstrators, technology readiness was only a secondary focus of this initiative. In fact, TPI Composites (Scottsdale, AZ, US) turned down an opportunity to participate in SuperTruck I specifically because the principal investigator’s approach seemed to be “a one-off show vehicle with no path to production,” Todd Altman, senior director of strategic markets for TPI Composites, recalls. The company is concerned whether new technologies can be “productized.” The criterion, Altman says, is whether “the value the technology provides buys it onto a production vehicle platform.”

Read more about the future of composites in long-haul trucks and trailers in the Nov. 2018 article “”

Related Content

TPI manufactures all-composite Kenworth SuperTruck 2 cab

Class 8 diesel truck, now with a 20% lighter cab, achieves 136% freight efficiency improvement.

Read More“Structured air” TPS safeguards composite structures

Powered by an 85% air/15% pure polyimide aerogel, Blueshift’s novel material system protects structures during transient thermal events from -200°C to beyond 2400°C for rockets, battery boxes and more.

Read MoreASCEND program completion: Transforming the U.K.'s high-rate composites manufacturing capability

GKN Aerospace, McLaren Automotive and U.K. partners chart the final chapter of the 4-year, £39.6 million ASCEND program, which accomplished significant progress in high-rate production, Industry 4.0 and sustainable composites manufacturing.

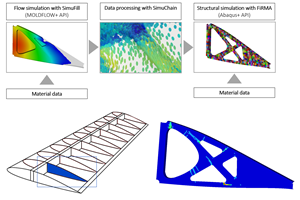

Read MoreImproving carbon fiber SMC simulation for aerospace parts

Simutence and Engenuity demonstrate a virtual process chain enabling evaluation of process-induced fiber orientations for improved structural simulation and failure load prediction of a composite wing rib.

Read MoreRead Next

Ceramic matrix composites: Faster, cheaper, higher temperature

New players proliferate, increasing CMC materials and manufacturing capacity, novel processes and automation to meet demand for higher part volumes and performance.

Read MoreNext-gen fan blades: Hybrid twin RTM, printed sensors, laser shock disassembly

MORPHO project demonstrates blade with 20% faster RTM cure cycle, uses AI-based monitoring for improved maintenance/life cycle management and proves laser shock disassembly for recycling.

Read MoreCutting 100 pounds, certification time for the X-59 nose cone

Swift Engineering used HyperX software to remove 100 pounds from 38-foot graphite/epoxy cored nose cone for X-59 supersonic aircraft.

Read More