Woven fabrics: The basics

For composite applications requiring more than one fiber orientation, woven fabrics can be useful. This primer outlines the basics of woven fabrics and different types.

Editor’s note: This content was originally published on NetComposites.com. NetComposites was acquired by ÂÌñÏ×ÆÞ’s parent company, Gardner Business Media, in February 2020.

For composites manufacturing applications where more than one fiber orientation is required, a fabric combining 0-degree and 90-degree fiber orientations is useful.

Woven fabrics are produced by the interlacing of warp (0-degree) fibers and weft (90-degree) fibers in a regular pattern or weave style. The fabric’s integrity is maintained by the mechanical interlocking of the fibers. Drape (the ability of a fabric to conform to a complex surface), surface smoothness and stability of a fabric are controlled primarily by the weave style. The following is a description of some of the more commonly found weave styles:

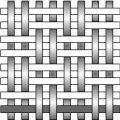

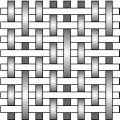

Plain weave

Plain weave

Each warp fiber passes alternately under and over each weft fiber. The fabric is symmetrical, with good stability and reasonable porosity. However, it is the most difficult of the weaves to drape, and the high level of fiber crimp imparts relatively low mechanical properties compared with the other weave styles. With large fibers (high tex) this weave style gives excessive crimp and therefore it tends not to be used for very heavy fabrics.

Twill weave

Twill weave

One or more warp fibers alternately weave over and under two or more weft fibers in a regular repeated manner. This produces the visual effect of a straight or broken diagonal ‘rib’ to the fabric. Superior wet out and drape is seen in the twill weave over the plain weave with only a small reduction in stability. With reduced crimp, the fabric also has a smoother surface and slightly higher mechanical properties.

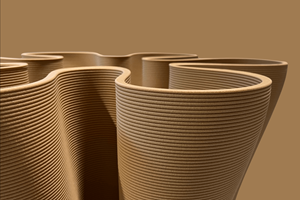

Satin weave

Satin weave

Satin weaves are fundamentally twill weaves modified to produce fewer intersections of warp and weft. The ‘harness’ number used in the designation (typically 4, 5 and 8) is the total number of fibers crossed and passed under, before the fiber repeats the pattern. A ‘crowsfoot’ weave is a form of satin weave with a different stagger in the re-peat pattern. Satin weaves are very flat, have good wet out and a high degree of drape. The low crimp gives good mechanical properties. Satin weaves allow fibers to be woven in the closest proximity and can produce fabrics with a close ‘tight’ weave. However, the style’s low stability and asymmetry needs to be considered. The asymmetry causes one face of the fabric to have fiber running predominantly in the warp direction while the other face has fibers running predominantly in the weft direction. Care must be taken in assembling multiple layers of these fabrics to ensure that stresses are not built into the component through this asymmetric effect.

Basket weave

Basket weave

Basket weave is fundamentally the same as plain weave except that two or more warp fibers alternately interlace with two or more weft fibers. An arrangement of two warps crossing two wefts is designated 2×2 basket, but the arrangement of fiber need not be symmetrical. Therefore it is possible to have 8×2, 5×4, etc. Basket weave is flatter, and, through less crimp, stronger than a plain weave, but less stable. It must be used on heavy weight fabrics made with thick (high tex) fibers to avoid excessive crimping.

Leno weave

Leno weave

Leno weave improves the stability in ‘open’ fabrics which have a low fiber count. A form of plain weave in which adjacent warp fibers are twisted around consecutive weft fibers to form a spiral pair, effectively ‘locking’ each weft in place. Fabrics in leno weave are normally used in con-junction with other weave styles because if used alone their openness could not produce an effective composite component.

Mock Leno weave

Mock leno weave

A version of plain weave in which occasional warp fibers, at regular intervals but usually several fibers apart, deviate from the alternate under-over interlacing and instead interlace every two or more fibers. This happens with similar frequency in the weft direction, and the overall effect is a fabric with increased thickness, rougher surface and additional porosity.

Woven glass yarn fabrics vs. woven rovings

Yarn-based fabrics generally give higher strengths per unit weight than roving, and being generally finer, produce fabrics at the lighter end of the available weight range. Woven rovings are less expensive to produce and can wet out more effectively. However, since they are available only in heavier texes, they can only produce fabrics at the medium to heavy end of the available weight range, and are thus more suitable for thick, heavier laminates.

Related Content

Revisiting the OceanGate Titan disaster

A year has passed since the tragic loss of the Titan submersible that claimed the lives of five people. What lessons have been learned from the disaster?

Read MoreLow-cost, efficient CFRP anisogrid lattice structures

CIRA uses patented parallel winding, dry fiber, silicone tooling and resin infusion to cut labor for lightweight, heavily loaded space applications.

Read MoreSulapac introduces Sulapac Flow 1.7 to replace PLA, ABS and PP in FDM, FGF

Available as filament and granules for extrusion, new wood composite matches properties yet is compostable, eliminates microplastics and reduces carbon footprint.

Read MoreOtto Aviation launches Phantom 3500 business jet with all-composite airframe from Leonardo

Promising 60% less fuel burn and 90% less emissions using SAF, the super-laminar flow design with windowless fuselage will be built using RTM in Florida facility with certification slated for 2030.

Read MoreRead Next

Scaling up, optimizing the flax fiber composite camper

Greenlander’s Sherpa RV cab, which is largely constructed from flax fiber/bio-epoxy sandwich panels, nears commercial production readiness and next-generation scale-up.

Read MoreCutting 100 pounds, certification time for the X-59 nose cone

Swift Engineering used HyperX software to remove 100 pounds from 38-foot graphite/epoxy cored nose cone for X-59 supersonic aircraft.

Read MoreNext-gen fan blades: Hybrid twin RTM, printed sensors, laser shock disassembly

MORPHO project demonstrates blade with 20% faster RTM cure cycle, uses AI-based monitoring for improved maintenance/life cycle management and proves laser shock disassembly for recycling.

Read More